Huge construction cranes stand out against the fading light of the skyline of Forest Park Southeast, a neighborhood at the center of St. Louis. They loom like enormous guardians watching over a popular stretch of Manchester Avenue lit by marquees that say “The Grove,” the neighborhood’s lively entertainment strip.

A quarter century ago, residents of Forest Park Southeast were afraid to walk down the streets at night, and visitors locked their car doors even while driving through during the day. Now, after decades of decline, developers are building a vibrant community atop a dying one, and as pieces of the old mesh with the new, a unique streetscape is emerging where abandoned houses and modern architecture seem at home next to each other.

In The Grove, business is booming, residents and visitors fi ll the streets, and shop owners, chefs, and barkeeps barely keep up with demand. Many low-income residents are staying, and high-income residents are moving in. The Grove is a tiny revolution shaking up housing in the United States.

As night falls over The Grove on Manchester Avenue, shop signs flicker on, and bar lights twinkle on. A murmur of laughter and conversation floats down from the Urban Chestnut Brewing Company’s porch as the sound of machinery at Madison Farms Butter Company fades with the daylight. Already, a line of people wrap around the block in front of The Ready Room, an indie music venue. The smell of baking dough wafts from Sauce on the Side. A couple of shops down, drag queens prep their makeup for tonight’s show, and children play a few blocks away at Lamb’s Bride, a 24-hour day care. Teens practice softball at the Cardinals Care Baseball Field a stroll away from Manchester, where murals decorate buildings on every block.

The neighborhood is in the middle of an explosive growth spurt. Cranes dotting the skyline aren’t the only visible markers of this evolution; on some blocks, it seems every fourth house is being remodeled or removed to make room for new construction. The sounds of power tools and demolition crews echo o the other structures. In the last 10 years, The Grove and its neighborhood have experienced 270,000 square feet of development, and more is coming.

The Grove itself is hip but approachable, with shopping and lunch spots bustling by day and bars and music venues sparkling by night. At City Boutique, shoppers can buy unique women’s fashion pieces. A new kitchen supply store, Lemon Gem, is as warm and welcoming as its cheery yellow paint job. Famous local chefs frequent Rise Coffee House, sipping the beanery’s locally roasted brews. A tiny nonprofit grocer, City Greens, peddles local meats, produce, and farmer-made products such as jams and goat’s milk soaps.

The Grove’s soul comes out at night when marquees bathe Manchester in a soft glow. The area’s famous gay bars pump out danceable beats, and their barstools fill up with both gay and straight customers. Ethnic restaurants and pubs open their doors for dinner. The best hummus in St. Louis is at Sameem Afghan, and Everest Café & Bar’s menu offers Indian, Nepalese, and Korean food. Music lovers can step back in time with a trip to The Monocle, an upscale bar with a refined vibe that hosts open-mic nights and cabarets.

The commercial success is spreading quickly. Manchester is home to dozens of annual festivals and events. In June, beloved chef Rick Lewis announced he left Southern to open a restaurant on Manchester called Grace. A new bakery is coming soon as well, and more developments in Forest Park Southeast are in the works. At The Grove’s entrance, what was once a broken parking lot is becoming a mixed-use, seven-story building that will house shops, office space, and apartments with a parking garage.

All this concrete is a far cry from the area’s verdant beginnings. In the 19th century, Forest Park Southeast was known as Rock Spring, a wooded place St. Louisans visited to relax and unwind near the waters of Mill Creek. In the 1850s, the Missouri Pacific railroad came to the area, connecting it to Jefferson City and beyond, allowing for an increase in commercial endeavors. Adams Elementary School, the St. Louis Public School that still serves preschool through fifth grade, was built here in 1899. In the 1930s, a housing boom began. Commercial growth peaked in the 1950s.

In the years following World War II, white residents slowly left the neighborhood for the suburbs, drawn there by the promise of big homes with low prices and wooed by Federal Housing Administration programs. As affluent families exited Forest Park Southeast, the area’s retailers and industries departed as well, taking their tax dollars with them. The community that was left behind rapidly saw dwindling economic and education opportunities. By the 1980s, the neighborhood was known more for its high crime rate than its flourishing community.

Lewis Claybon, an effervescent middle-aged black man who lives, works, and worships in Forest Park Southeast, first arrived in 1987 as a construction worker. At that point, developers were just beginning to build. “Back then, it was the worst place to live—shootings, drugs, violence,” he says. “You can’t appreciate the whole new neighborhood it is right now unless you understand how violent it was back in the ’80s. You won’t appreciate the peace and quiet we have now.”

John Oberkramer, co-owner of Just John, one of The Grove’s most famous gay nightclubs, is a muscular white man in his 50s. In the late 1980s, he lived outside of St. Louis and worked at Washington University. He drove down Manchester on his daily commute. “I would roll my windows up, lock my doors, and pray that I made it through without getting carjacked or shot at,” he says.

John now lives in Forest Park Southeast. His 19 years at Just John have given him a front-row seat to the changes. “It just always seemed like it was getting better and better and better and better,” he says. “The past five years have been an explosion, but it was growing for a decade before that.”

The Washington University Medical Center Redevelopment Corporation (WUMCRC) is responsible for much of the development in Forest Park Southeast. A few decades ago, after the white exodus to the suburbs, the group began to develop economic and housing opportunities near its campus. The city gave the organization jurisdiction over zoning and land development of six blocks of Forest Park Southeast. The redevelopment corporation bought up abandoned homes and sold them to developers who agreed to restore the buildings. Recently, WUMCRC has taken on a more supportive role, with the organization paying for a community center for the Boys & Girls Club and streetscape improvements.

Lewis has witnessed Forest Park Southeast’s rebirth under the influence of WUMCRC. He’s grateful that developers invested in his neighborhood. “I don’t even know why they did it because it was so bad, but I’m glad they did,” he says. “It’s more of a community now. People are more cordial; people can walk safely at nighttime. Everything we enjoy now is because of the development that’s come in and made it a new neighborhood. The crime came and went, and they shut it down and made room for improvement.”

The Grove’s redevelopment will bring increased property value for residents and businesses and stabilize the neighborhood’s economy, but some fear it reduces the area’s diversity. Critics point to a history of development where gentrification lured wealthy white families, forcing low-income renters out of the area and erasing the community and culture of the people who lived and worked there before the construction crews arrived. Another outcome could be that a fluent residents will build up an area and then not stick around to make sure the benefits last.

John A. Wright Sr., a Fulbright Scholar and former interim superintendant of St. Louis Public Schools, is the author of 13 books on St. Louis history, including St. Louis: Disappearing Black Communities. He says the story of The Grove has played out before. “Look at LaClede Town,” he says, referencing a 1960s US Department of Housing and Urban Development experiment to create a diverse neighborhood in both race and income. Like The Grove, LaClede Town was built on the ruins of a once black neighborhood near St. Louis University. Within just a couple of decades, it was shuttered and condemned. When the dust settled from families leaving and taking their resources with them, the folks left behind in a crumbling neighborhood were mostly black.

John Wright says white populations will generally flee a neighborhood if the black population is greater than 36 percent. “Race trumped everything. That percentage will control who goes and who stays … along with fear.” Banks and markets also play a role in selecting for race and creating segregated communities, he says.

That’s why community groups and organizations—such as the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council and the Coalition for Neighborhood Diversity and Housing Justice—are trying to maintain the diversity of gentrified neighborhoods to steer growth and economy to benefit every resident. Molly Metzger is an assistant professor at Washington University’s George Warren Brown School of Social Work, where she chairs the concentration in social and economic development. She is a member of the Coalition for Neighborhood Diversity and Housing Justice. “Gentrification is happening and has been heavily subsidized through tax abatement,” she says. “If we really care about preserving diversity and affordable housing in this neighborhood, we need to … do a better job of supporting affordable rental and ownership opportunities. (There) are passionate, engaged people who care about diversity. We’re in a divided moment, politically and racially, in this country. In neighborhoods like Forest Park Southeast, if we are able to sustain that diversity, it’s an opportunity to show the region and the country that it’s possible to exist together despite our differences.”

There are many benefits of diversity in communities, especially for culture and innovation. “We deprive ourselves of the benefits of living in a truly diversified community,” John Wright says. “I was talking to some folks about how they were able to make a life on very little money. Another family had it all. They both felt there was something they could learn from each other. And so, you begin to open doors.”

WUMCRC Executive Director Brian Phillips says his organization is dedicated to maintaining diversity in Forest Park Southeast. In the late ’90s, WUMCRC built affordable salable and rentable units before starting on more profitable projects. This was purposeful, Brian says. “People understand that they’re moving into a mixed-income neighborhood. We see a great deal of harmony that way.”

The plan produced about 55 units of affordable for-sale housing between 1997 and 2001, Brian says. “And from our earliest efforts, even on to today, we continue to work with area partners to provide affordable rental housing,” he says. “The first set of those were renewed for affordability for another 15 years just recently.” Additionally, the group has produced 96 units of affordable senior housing. Brian adds that WUMCRC has partnered with nonprofit housing firm Rise Community Development to build 50 affordable apartments through an $11.5 million project called Adam’s Grove.

The Forest Park Southeast neighborhood is a diverse blend of industry, services, community centers, restaurants, and shops scattered among modern homes next to traditional homes next to dilapidated buildings. Each building somehow looks like it belongs in the mix, just as the people here, all so different, all appear to belong together. “Latinos, blacks, whites, gays—everybody lives here in harmony,” Lewis says. “Nobody bothers nobody. We’re all people. We just do what we do, let it fl ow, enjoy life, be at peace.”

Perhaps what is happening in Forest Park Southeast is a mix of gentrification and commitment to diversity, a modern-day LaClede Town. The big question is if the neighborhood will sustain its diversity. The community will find out with the next couple of censuses.

Until then, Lewis and John can’t help but admire what their world is becoming. “Life on Manchester—the new life that it has now, a whole different personality—is the best thing about the neighborhood,” Lewis says as he walks toward Manchester from his home. It’s Friday at dusk in The Grove, and he’s going to see if a recently constructed restaurant is open yet. Music spills out of doorways, and the street is already full of people of various backgrounds headed into bars and restaurants. He glances up the street toward an empty area that used to be a community garden. The garden, still used by residents and students, has been moved to a spot behind the school. Instead of vegetables and flowers, new buildings will soon sprout up in the garden’s old lot.

“They bought out the packaging company at the light at Tower Grove and Vandeventer and will put up apartments,” Lewis says with excitement in his voice. “There’s so much being built. We’re going to be connected with South Grand, with Central West End, and the Loop. All this has been coming since 1987. Now it’s one of the best places in Missouri to live,” he adds.

“Development makes this neighborhood good,” he says. “And that helps St. Louis and the world. Every bad neighborhood hurts the world, and every good one helps it.”

Related Posts

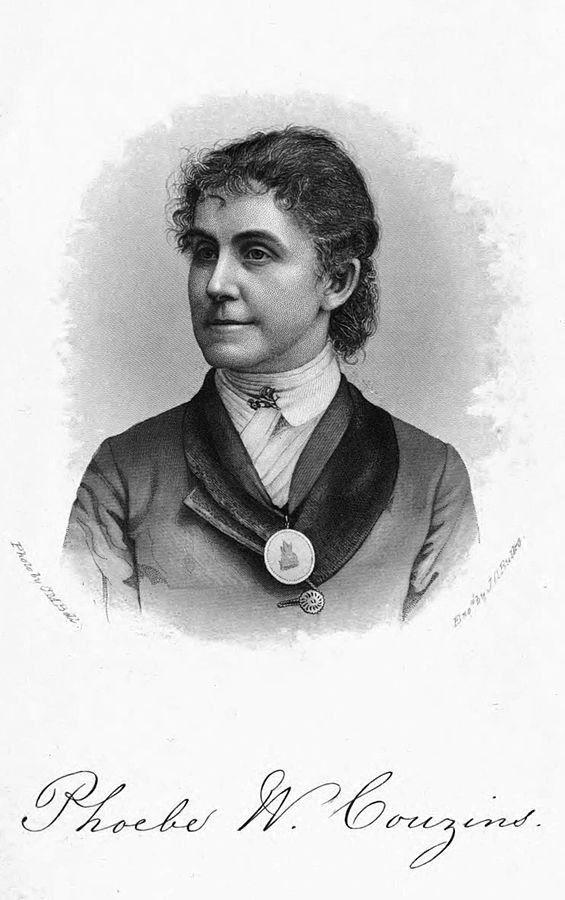

September 8, 1842

Phoebe Couzins was born in St. Louis. She went on to become one of the first female lawyers in the United States and the first woman to be appointed to the US Marshall. She earned a law degree from Washington University in St. Louis, and she is now buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

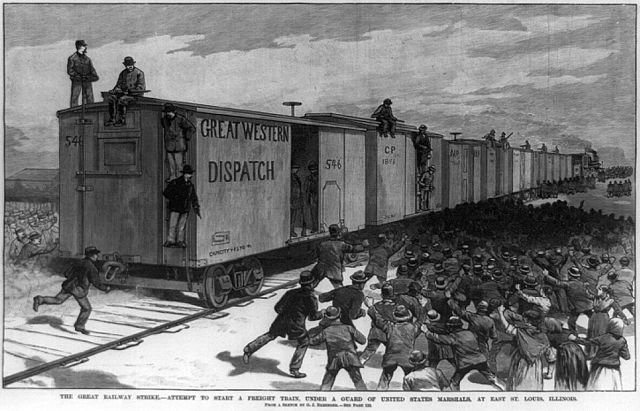

July 30, 1877

Days after the conclusion of the St. Louis general strike by the St. Louis Workingman's Party, the first general strike in the United States, the St. Louis County Council required all able-bodied males between the ages of twenty-one and fifty to work on the roads for six days each year. That day they also made another change; they raised the drinking age from sixteen to eighteen.

Here Are Our Favorite Places to Get Gooey Butter Cake in and Around St. Louis

Legends abound about the true origins of gooey butter cake, with one common denominator—like toasted ravioli, it is purported to be a mistake of glorious proportions.