The beauty of trails is found in the slow pace, which allows riders to truly experience places. The Rock Island Trail, connecting the greater Kansas City area to Missouri’s Katy Trail system, is an experience to savor whether you are walking, cycling, or on horseback.

For decades, this western Missouri connection has been a holy grail sought by trail advocates. Officially dubbed the Rock Island Spur of the Katy Trail State Park, the 47.5-mile addition carves a path from a new trailhead in western Pleasant Hill to Windsor, a city-stop along the Katy. Thus, the Katy is one step closer to stretching across the entire state. With the westward connection complete, trail zealots have set their sights on expanding the Rock Island Trail to St. Louis, creating a more than 400-mile Katy Trail loop that would cover nearly all of middle Missouri.

The Katy is the nation’s longest “rail-trail,” a trail birthed from the ruins of a railroad. The Rock Island Spur, often called “the Rock,” was formed from the Rock Island railway system and adds more mileage to Missouri’s rail-trail systems. There are scattered reminders along the Rock that the path was once an important railroad. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources, which manages the spur, has maintained the evidence of the bygone railroad era with adornments such as light boxes, switches, grain elevators, and other equipment.

Since its opening last December, thousands already have found that the Rock Island Trail is “the road to ride,” a phrase taken from a 1920s spiritual about the Rock Island railway system. In 1957, Johnny Cash expanded the lyrics and ensured the song’s place in Americana history.

“Down the Rock Island Line, she’s a mighty good road, Rock Island Line, it’s the road to ride.”

Affectionately nicknamed the Rock Island Line for short, the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacifi c Railroad opened in 1852 between Chicago and Rock Island, Illinois. Within a half century, the line extended across Missouri and well into the southwest. In Missouri, the line was a “milk run” that literally carried milk and other farm commodities to market until the last train ran west out of Kansas City in the spring of 1980.

Pit Stops

Now considered part of the Katy Trail State Park—the longest and skinniest state park in America—the Rock Island Spur lies within a corridor of public property only about 100 feet wide in most places. Almost all the adjoining land is privately owned farmland.

Rock Island Trail is breathing new life into the small towns of Leeton, Windsor, Medford, Chilhowee, and Pleasant Hill. And the friendly folks who live along the Rock are ready for company.

“Bicycles will be everywhere next year,” prophesies Rodney Higgins from Chilhowee. Rodney, an eighty-three-year-old farmer who loves old tractors and his land, recalls meeting some Arizona cyclists while enjoying dinner with his family at a Clinton restaurant. “They were happy and fun,” he says. “Bad people are too lazy to ride a bike that far.”

Norval Netsch, a seventy-nine-year-old Renaissance man who lives near Bowen, owns one of the farms that hug the Rock Island Trail. Norval is a forester, biologist, and master craftsman with an endearing smile and quick laugh.

Norval returned to his land after a career as a fisheries biologist in Alaska. He now lives on the same land where he grew up. In 1948, he was baptized in a small pond that was recently dredged and restored near the trail. “When my sins were washed away, that may have been what filled that old pond up,” he jokes.

He and his wife, Jane, see the value of the trail that bisects their land. “My wife used to walk the road,” he says. “She loves the trail now.”

The Rock has added a new dynamic to the area that goes beyond split-up farmland. People such as Kim Henderson at Windsor are banking on the Rock’s promise to bring more passersby. Kim, an entrepreneur and community leader, already has skin in the game. She recently opened Kim’s Cabins to serve touring cyclists and anyone visiting the area. The comfortable and cheery cabins were built on the theory that if you build the trail, they will come. With the Rock open, “Windsor has become a destination,” Kim says. “Folks are driving from outside the area to Pleasant Hill, parking and riding down to stay the night, and riding back.”

Kim champions Windsor as a “great taste of small-town life, with friendly people and beautiful countryside.” Trail users can enjoy beautiful Farrington Park with fi shing and rental boats on the lake that used to supply water to steam locomotives on the Rock Island Line. They can also visit Amish quilt shops and a weekly farmers’ market.

Situated at the junction of the Katy Trail and the Rock Island Spur, Windsor is set to become Missouri’s epicenter of the rails-to-trail systems. From Windsor, folks can now pedal in three separate directions. Heading southwest on the Katy will take you to Clinton, the terminus of the Katy Trail. Head east, and you are on your way to Boonville and the rest of the Katy. Go west, young-at-heart men and women, and you will reach Pleasant Hill.

The western terminus of the Rock Island Trail is in downtown Pleasant Hill near the Cass County Fairgrounds. A very short drive from Kansas City, Pleasant Hill is as quaint as it sounds. Cafés, shops, and bars give cyclists a reason to linger awhile. If you need service or even a new bike, get help at the New Town Bicycle and Coffee Shop. Check out the vintage bikes at Retro on the Rails in the old historic depot, too.

Towns along the Rock are embracing trail users. Riders can expect clean restrooms and basic community services. Services are excellent in Windsor, Leeton, and Pleasant Hill. Stop for pie at the Leeton Café on Main Street near the Leeton Trailhead. Currently, Medford is the only trailhead without a place to grab a quick bite or refuel with a sports drink.

Riding the (T)rails

The Rock provides a new trail experience, not a rinse-and-repeat if you have already logged a lot of miles on the Katy.

Far from the Missouri River, the Rock’s identity, unlike the Katy, is not tied to the muddy waters. Instead, the Rock is a throwback to simpler times and pastoral scenes. Visitors are embraced by a landscape devoted to feeding a nation: native grasses, wheat, corn, and soybeans.

The basic trail specs of the Rock and the Katy are very similar. The Rock’s eight-foot-wide surface is limestone pug, a very fine gravel over a larger base. Most cyclists can be comfortable taking their best bikes on the trail as it matures. Although there are a few clearly marked road and farm crossings, for the most part, there is no vehicle traffic. Wetlands, waterways, and tree canopy grace much of the trail, providing shade and edge habitat for birds and animals. The railroad tracks were elevated to maintain a 2 to 5 percent grade for locomotives, so that elevation today provides an interesting perspective of the surrounding treetops and forest floor far below—with almost no hills.

The spur is open to equestrian use. Most horse enthusiasts will ride a trail like the Rock seasonally, so cyclists and walkers are more likely to encounter riders in the fall and winter. Horses always have the right of way. There’s an old saying that the only things that spook a horse are things that move and things that don’t, so take care to gently alert equestrians of your presence before passing from the rear.

With the landscape and smattering of towns along the way, the Rock is indeed a “mighty good road,” as the song says. Trail users can experience a slice of Missouriana usually only glimpsed at fifty-five miles per hour.

Norval encourages trail riders who pass his land to take their time and enjoy the slow pace. Sitting on his “Contemplation Rock” in view of the trail, Norval says he “feels kinda sorry” for the riders he sees with their heads down and their toes clipped in the pedals.

“Look around and enjoy the land,” he advises. “Look at the birds. Watch out for snakes—my wife saw three the other day. Smell the roses.”

The author, Bill Bryan, is the former director of Missouri State Parks. He left office in January, after serving for more than eight years. His tenure included expanding the state park system and creating the Rock Island Spur.

Related Posts

James Sidney Rollins is Born: April 19, 1812

James S. Rollins was born on this day. Many recognize Rollins as the Father of the University of Missouri.

Game On!

They say the house always wins, but community takes the jackpot at Vintage Vegas Casino Night. Sponsored by Vision Carthage, the event features food, drink, and plenty of casino-style fun. Proceeds benefit local charitable initiatives.

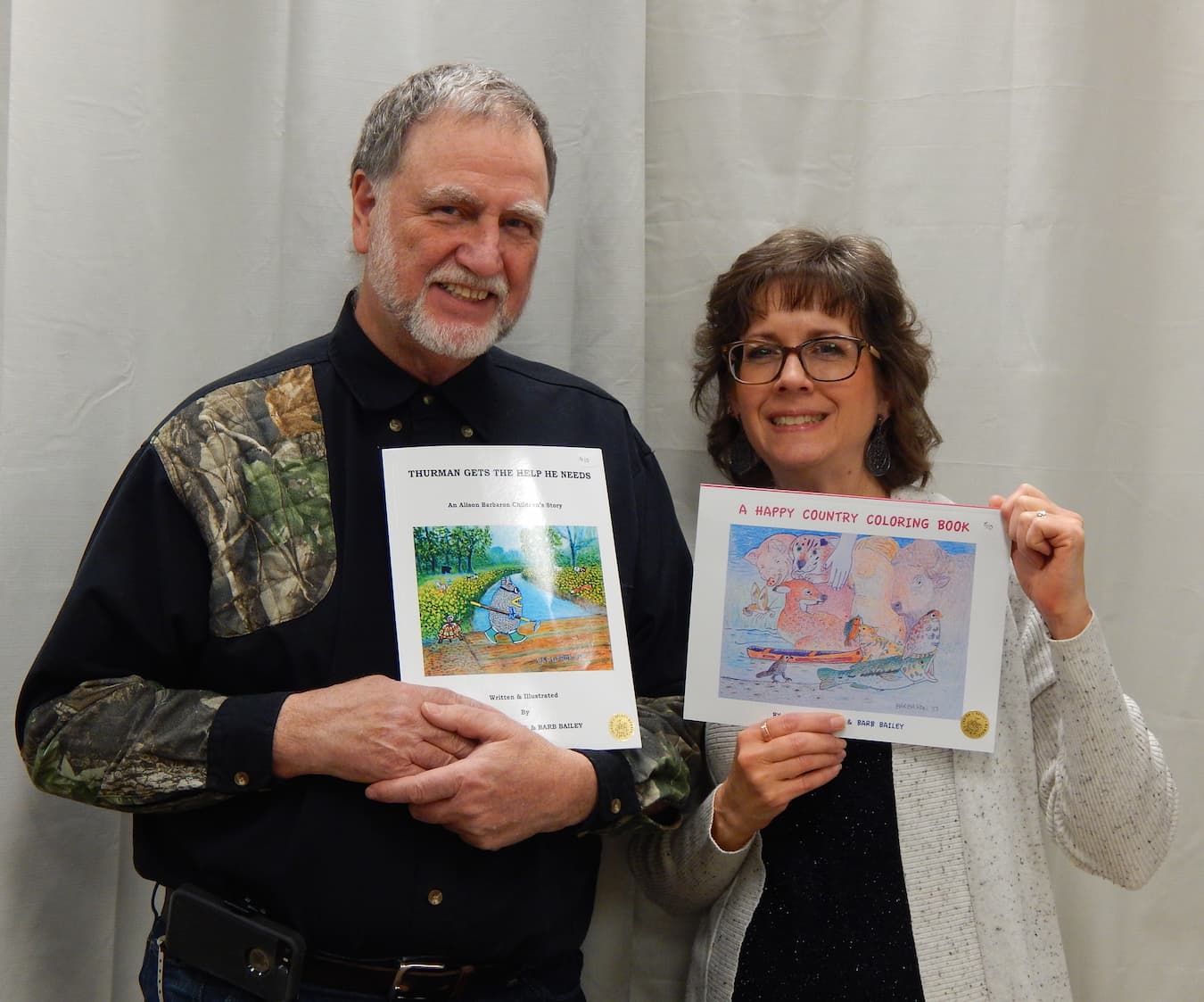

Better Together

These two Cape Girardeau painters write and illustrate children's books in an unconventionally collaborative way. Their method is a fast-paced give-and-take that requires absolute trust, open minds, and a willingness to pick up and pivot.

MO News is Good News – April 19, 2024

Big things are always happening in Missouri. In this week’s headline roundup, we’ve got big bugs, big fish, big money, and your big chance to land on national TV.