Females fuel America’s wine industry: women buy 57 percent of the wine consumed in this country. But the ladies are not only buying and drinking wine; they’re making it, too. Women account for a small but growing number of winemakers in Missouri’s 132 wineries. Their motivations for working in the wine industry are as varied as their backgrounds: some do it for the science, some call it a retirement plan, others are keeping alive a family tradition, and some just want a little weekend fun. Whatever their reasons, they share a love of creating a good Missouri wine. Here’s a look at five who took different paths to the vineyard.

Whitney Schmidt • Vox Vineyards • Kansas City

Winemaking is a 7,400-year-old craft, and in all those years, the process hasn’t changed much. Whitney Schmidt of Vox Vineyards in Kansas City spends her days researching how to improve winemaking in Missouri and around the world. She wants to find ways to work with the local ecology while growing grapes, aiming to use fewer harmful chemicals on the vines, lengthening the industry’s sustainability.

“Vox just got a grant last year to do research because every experiment we do that’s different than the conventional way of maintaining a vineyard is a huge risk,” Whitney says. “So the grant is very helpful in helping us to achieve something.”

Researching sustainable methods of vineyard agriculture isn’t a moneymaker for the vineyard. “But the focus for Vox from the beginning has been to increase the diversity of grapes grown in the US,” Whitney says. The grapes currently grown in the United States were bred in the late 1800s by horticulturalist T. V. Munson.

“He did work in Missouri, Texas, and Nebraska,” she says. Some of his best work was developing the rootstock now grown in vineyards around the nation. His secondary work was developing grape cultivars bred from native species to produce high-quality wine that would also grow in harsh conditions with high humidity or extremely low temperatures. He also bred some with Pierce’s disease resistance, which is becoming a bigger issue now. Pierce’s disease is caused by a bacteria spread by leafhoppers.

Whitney is building on Munson’s work of creating disease-resistance grapes. In college, she worked with Mizzou’s Grape and Wine Institute. “I worked on different growing methods to increase quality, studying sun exposure on fruit and the aroma compound development,” she says.

As a scientist, she spends most of her time in the vineyard’s lab, but, she says, “I need a close relationship with the vines to produce great wines.” She’s out in the vineyard almost every day, handpicking and sampling. To analyze the grapes, Whitney will put one into her mouth and begin to pull apart the components to assess them. There are three components of a grape: the skin, pulp, and seeds.

“They’re all contributing different things, so it gets really intricate,” she says. For example, chewing the skins tells her what kind of aromas should be in the wine when it’s finished. Being able to assess the components of the grapes before pressing lets her predict how successful a wine will be.

Excellent grapes make excellent wines. With her profound understanding of grapes and development of new growing methods, Whitney may find ways to advance this ancient craft.

Debbie Van Till • Van Till Family Farm Winery • Rayville

After a long day in the fields of their vegetable farm in California many years ago, Debbie Van Till looked at her husband, Cliff, and said, “Let’s start a winery so we don’t have to harvest on our knees anymore.” They eventually opened a Missouri winery, Van Till Family Farm Winery. She and Cliff have a 1-acre vineyard where they grow and test different grape varieties. They sell wood-fired pizzas paired with the wines they’ve bottled. They grow most of the pizzas’ toppings and serve everything in an indoor wine garden overflowing with plants that are always in bloom: geraniums, citrus trees, and ivy.

In the lab, Debbie develops wine with her visitors’ input. “I have customers try what we’re developing. They’re generally very honest. In the wine garden, we’ll run into people, and I’ll give them a chemistry flask. They’ll taste it and tell us what they think. If somebody standing there says, ‘I would pay $40 for a bottle of that,’ then I think, okay, that’s a nice wine.’”

She’s developed a network of friends and colleagues from customers and other women winemakers. Five years ago, they developed the Northwest Missouri Wine Trail. “It’s surprising how many women there are in the industry,” Debbie says.

Bonnie Hemman • Hemman Winery • Brazeau

Bonnie and Doug Hemman’s children didn’t spend Saturday mornings watching cartoons while eating Cap’n Crunch. They were up early and out doing chores in the family’s vineyard. “They didn’t necessarily like it, but they were in it,” Bonnie says. “I couldn’t leave them at home by themselves.” For the past 17 years, the couple has spent every weekend at the vineyard and winery while holding down regular 9-to-5 jobs during the week and balancing family responsibilities.

Bonnie and Doug began selling their wine to the public 15 years ago, but the Hemman family had been making wine for a long time. The sweet wine made by Doug’s grandfather, his parents, and then Bonnie and him was popular among each generation’s friends, who urged the family to make it for sale. The Hemmans do it all together. They grow the grapes, harvest, press, process, bottle, label, cork, and handle the daily chores that come with running a business—relying on help from volunteer harvesters once a year and advice from fellow winemakers.

The vineyards in Missouri cooperate with each other, Bonnie says. Together, the southeast Missouri winemakers developed the Mississippi River Hills Wine Trail. “People really try to help each other in this industry,” Bonnie says, “because we’re trying to accomplish the same thing: make good wine.”

Cyndy Keesee & Steffi e Littlefield • Edg-Clif Winery • Potosi

Steffie Littlefield and Cyndy Keesee may have lived in many places, but only one place has ever been home: their family’s farm just outside Potosi. As children, the sisters’ only vacations were on the farm, hiking its ridges and tubing its waterways. As young adults who moved away to pursue careers, they dreamed of one day moving back and making a living from the farm. In 2008, they began to make the dream come true. Together with their husbands and children, they moved home to Missouri and planted vines, turning the farm into Edg-Clif Winery, which was bottling by 2010. “We can rely on each other because we trust each other in this business,” Steffie says. “Cyndy’s skills in the winery—I know her abilities. I don’t have to second-guess that. I know she feels the same way about decisions I make on the business and vineyard side.”

To turn their family farm, which they had leased out to a bison producer for the past 65 years, into a viable winery, the women worked with University of Missouri Extension Service. “They helped us design the layout of the vineyards, which is a free part of their service to educate and promote sustainable agricultural goods in the state,” Cyndy says.

Steffie’s experience as a horticulturalist allows the vineyard to produce grapes that are just right for its soil. “We grow three different French-American hybrid Chambourcin,” she says. “We’re very small. We do shy of 1,000 cases of wine a year, give or take. Thanks to our good viticulture practices, we are able to sell some of our Chambourchin, which is nice because we can’t use it all.”

Edg-Clif’s small size gives the sisters advantages in the wine market, they say. “We don’t add things to wine that we don’t need to because we’re not dealing with thousands and thousands of gallons at a time,” Cyndy says. “There’s a difference at a bakery buying hand-crafted bread versus mass-produced— wine is the same. Everything here is done by hand, so we hand-sort and bring in the grapes we want for that particular wine.”

The sisters have also delved into making different drinks: beer and perry, an English-style wine made from pears that Steffie describes as dry and slightly effervescent.

After winning a few awards for their wines, the sisters say they feel satisfied knowing they achieved their long-term goal of making their family’s 90-year-old farm viable. “We still choose to spend our time at the farm,” Cyndy says. “It’s beautiful, and we just love it down here.” Whether they’re working on the farm or camping out in its wilder spots, the sisters agree, “This is where we like to be.”

Top photo by Nacho Domínguez Argenta on Unsplash

Related Posts

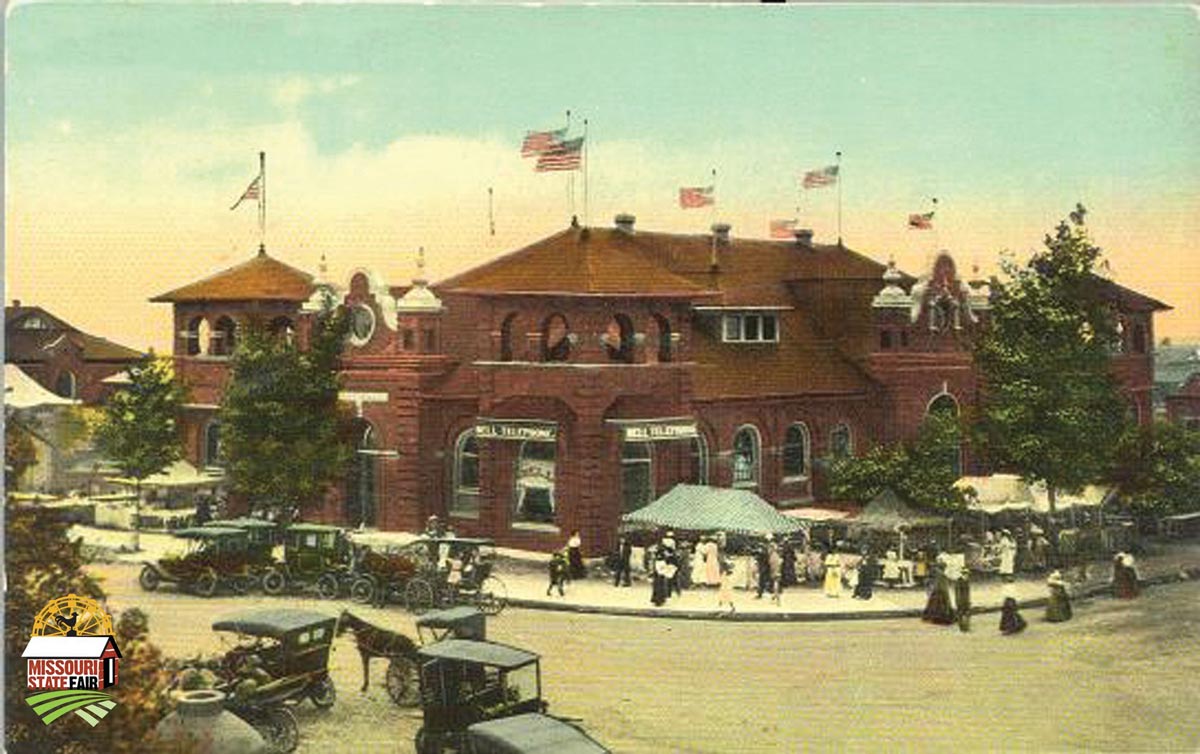

7 Time-Honored State Fair Traditions

Each year there’s something new to see, and yet some components of the Fair date back from before Missouri actually had a designated State Fair. Let’s take a walk through time and look at some of the State Fair’s most proud traditions.

Meet the Missouri Veteran Who Makes Gold-Medal Burgers

When Sedalia resident Terry Shull won the 2017 Missouri State Fair Burger Contest, he did it his way. With 17 years of cooking under his belt, Terry has learned to experiment and try new recipes.

Meet Missouri Farmers Kalena and Billy Bruce

Meet some of the farmers raising the beef you eat right here in Missouri, plus, we share a recipe for slow-cooker shredded beef.