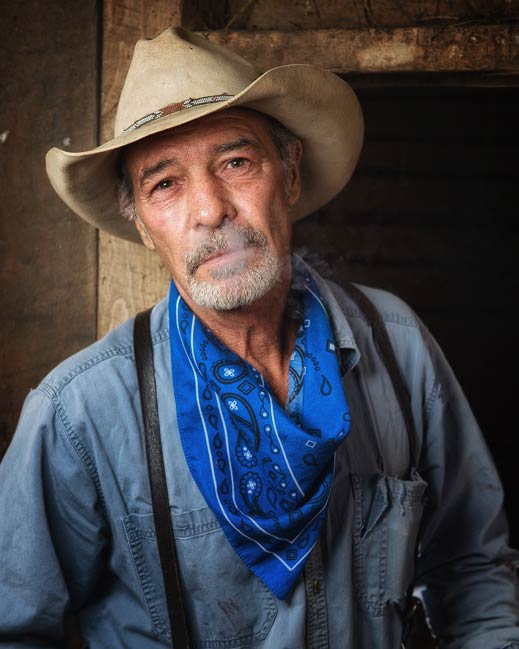

“When I was a kid,” says 64-year-old Randy Cate, “if there was a horse in the neighborhood that needed to be broke, folks’d say ‘take it over to the Cate boys, and they’ll get it broke.’”

Growing up in Glendale, Arizona, the Cate boys—Randy and his two brothers—were often pressed into service to “ride the buck o ” a horse. When they had tamed the steed, their father would introduce it to his pony ring, a family side business that augmented their father’s carpentry work. The Cates traveled around the country, selling pony rides at fairs and grocery store parking lots. Their mother played the guitar to entertain folks. Randy’s hardworking parents raised their children to respect honest work, o ering such wise advice as “never ever look down on another man, unless you’re picking him up.”

On April 14, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum will lift up Randy to honor him for his “unwavering commitment to the American West’s future,” when it presents the lifelong cowboy with the Chester A. Reynolds Award at the museum’s Western Heritage Awards ceremony in Oklahoma City.

Randy is the first Missourian to receive the prestigious accolade. For the Webster County farrier, it has been a cross-country journey to the pinnacle of cowboy honors.

Rodeos & Ranches

Randy quit school after the ninth grade to work with his dad as a carpenter. He’d worked with horses since he was 6 years old and began shoeing horses part time when he was 20. His parents moved to the Missouri Bootheel in the early ’70s, about the time Randy thought he’d try riding rough stock on the rodeo circuit to make a few extra dollars. His dad would have liked to see him do something other than cowboying, he says, because, he told him, “that ain’t gonna take you anywhere.”

Rodeo life is a tough way to make a living and Randy found he wasn’t good enough to win more than a buckle. An accident in Sikeston in 1978 brought clarity to his career plans when Randy was thrown from a bronco named Snow Man, injuring his neck and tearing his meniscus. He decided it was a good time to hang up his rigging.

“I’d been thrown before the eight-second whistle blew, so I wasn’t going to get any money,” he recalls. “I was pretty beat up. My uncle said he wanted to see how I could shoe horses from a wheelchair.”

He took a job with farrier Terry Bradshaw in El Cerrito, California. “Terry was an old guy by the time he was in his 40s and could barely stand up,” Randy says. “He soon turned the business over to me because he’d done enough of that back-breaking work.”

Randy suddenly realized he was in charge of shoeing three hundred horses on his own, so he started reading everything he could find about the farrier trade. At the same time, he began picking up day work at nearby ranches to make extra money. Armed with a wider range of experience, he moved on to ranch work in Oklahoma.

“I worked as a herdsman at some of the biggest outfits in Oklahoma: the J-T, B & L’s Circle Y, the Arrowhead, the Davison Ranch, the Roos, and the Thompson Cattle Company,” he says. Despite his father’s warning, “It was my dream come true to be working as a cowboy.”

Always interested in learning more, Randy listened to old-time cowboys as he worked alongside them. He fondly remembers J.D. Pitcock, a top hand at one of the Red River Valley ranches. At the age of 74, J.D. was still making his living in the saddle. He taught Randy how to doctor cows with mastitis and the correct way to handle cattle without stirring them up.

“Ranch work was the best part of my life,” Randy says, but like nearly all of his experiences there wasn’t much money in it. He could have made more in the oil fields, but that didn’t suit him. He loved being outside on a nice day, working with cattle, and learning dierent handling techniques. “When my knife was sharp, it was a good day to castrate calves,” he says.

He worked on horseback, gathering large herds to separate calves for the ground crew to brand, castrate, deworm, and dehorn. A threering notebook, taped together, weather-beaten, and sweat-stained, reflects part of the cowboy’s story. Filled with notes on breeding and medicating cattle, as well as the locations of ponds, creeks, and back-country trails on wrinkled handdrawn maps, it serves as a testament of a life’s work in the saddle.

But the notebook was no resume, and Randy realized he needed to ride a school desk for a while if he wanted to graduate from cowhand to ranch manager. He successfully completed a course in cattle management and breeding in 1987 at the Graham School in Garnett, Kansas.

Show-Me Horseshoes

But then, Randy’s mother called from Missouri with a plea for help as his father neared the end of his life. With the understanding that he was giving up a budding career in the cattle industry, he moved to Missouri to care for his much-loved parents. There were no regrets.

“I didn’t have any trouble finding horses to shoe,” he says. “I was quickly covered up.”

By word-of-mouth, satisfied customers spread the word on Randy’s good work. He discovered the region’s biggest equine problem was foundering, which is mainly caused when horses are turned out to pasture too early in the springtime and overindulge on lush, green grass.

The resulting inflammation, called laminitis, is a debilitating condition that malforms the horse’s foot by putting added pressure on its coffin bone. A horse with laminitis will start to limp and eventually become crippled.

Over the past 20 years, Randy has used various shoeing techniques in his mission to bring foundered horses back to living healthy, active lives. On many occasions, he has been called as a last resort to evaluate what can be done with a stricken horse. He often works in concert with southwest Missouri veterinarians such as Richard Linn and Randy Spragg.

After locating the specific sore spot by squeezing around the aected area with a set of hoof-testers, he trims the area before daubing it with pine tar. He then fits the lame horse with a corrective shoe that he has fabricated with a bit of welded-on bar iron, using only enough nails to keep the shoe in place. The contoured shoe shifts pressure away from the sore spot by transferring weight o of it. Randy recommends that the horse’s hoofs be properly trimmed every four to six weeks. When used in the early stages of laminitis, his technique boasts a 98 percent turnaround rate in foundered horses. Intervention even in later stages of laminitis can make a horse more comfortable, he says.

With innovative techniques and creative equipment, Randy has helped countless horses and mules get back on their feet. Some, he allows, are easier to work with than others. His most dangerous experience was at an exotic animal ranch near Bruner when a mare cornered him. She reared up, he recalls, and all he could see was her navel. “Her hoofs could have split my head open, but thankfully she backed o ,” he says.

Since the 1970s, Randy has purchased and trained wild mustangs, with the goal of helping them become adoptable so they won’t be destroyed. It started with a group of 40 captured mustangs at a sale barn in Nevada. He had the background to train his bunch, although other buyers didn’t fare as well. He has continued to buy a wild mustang every year or so and train it to prepare for adoption.

The connection between horse and farrier runs deep. Randy recently met again a horse he had saved more than two decades ago by buying it for $5 over slaughter price. After performing corrective repair on one of the horse’s severely damaged hoofs, he sold it. Years later, a friend realized her horse had once belonged to Randy and got them back together.

Passing the Torch

From his Webster County base between Fordland and Seymour, Randy travels throughout the region to assist animals in trouble. He also o ers clinics and other services through his website, HelpMyLameHorse.net. A good portion of his farrier work takes place at Reasons Ranch near Sparta. His 22-year-old nephew, Colton Cate, works alongside his uncle, just as he has since he was 10 years old.

Colton does most of the hardest labor now, his uncle notes. “He’s the real show,” Randy says. “I only sell the peanuts.”

Photos by Ron McGinnis and courtesy Randy Cate

Related Posts

For That Special Someone

Lorry’s husband meant well when he bought her greeting cards for special occasions, but his failure to read the sentiment inside led to some hilarious blunders. She shares memories of his oddest choices, and tells how she finally got even.

Meet The Saddlemaking Cowboy Poet of Missouri

A widower since 2011, Martin still surrounds himself with the stock in the trade of saddle making. His workspace is as much a museum of leather crafting as it is a saddle shop.