In 1885, Ella Kate Ewing, a sensitive thirteen-year-old girl, stood six feet tall, alone on a stage in rural Scotland County, Missouri:

“My classmates chose me to recite the Declaration of Independence. I practiced for weeks … I heard voices from the crowd. ‘Would you look at that girl?’ cried one man. ‘She’s as tall as a barn!’”

“‘Her hands are as big as skillets,’ laughed a woman.

“‘I’ll tell you what that girl is,’ yelled a boy. ‘She’s a freak!’

“I ran off the stage in tears.”

Those words were written in Ella Kate’s voice by another Kate who also claims Missouri as her home. They are from noted children’s author Kate Klise in her 2010 book, Stand Straight, Ella Kate, illustrated by her sister M. Sarah Klise.

It’s no wonder that a writer like Kate would be drawn to the story of Ella Kate, the “Missouri Giantess.” Born in LaGrange in 1872, Ella stood eight feet four inches when fully grown and wore size 24 shoes. But it wasn’t what Ella Kate was that captured Kate Klise’s attention. It was, rather, who she was.

“The more I read about her, the more I saw that she was the hero of her own life,” Kate told me in a recent interview from her farm deep in the Missouri Ozarks near Mountain Home. “Ella Kate was devastated that day she took the stage, totally devastated. There is no question she wanted to hide from the world. But there was something within her that made her rise up—no pun intended.”

Eventually, as Ella Kate assumed her inevitable stature, word got out about the giant woman from Missouri whom many called “a freak.” When she was eighteen, a man from a Chicago “dime museum” (aka, a sideshow) offered her $1,000 to go on public display for a month. Kate Klise says that Benjamin Ewing’s response, as told by Ella Kate, was, “Nobody’s paying money to gawk at our girl!”

That may have been the moment that moved something deep inside Ella Kate, moved her out of the malaise and the hurt she felt into the person she truly was. She told her father, “If people were going to gawk, make them pay.” In 1893, she exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair, an event attended by twenty-seven million people.

In 1897, she joined Barnum & Bailey Circus on a nationwide tour. In an interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Ella Kate conceded, “It was terribly embarrassing to me at first but I have almost gotten used to it.”

Ella Kate used her earnings to help her parents pay off a loan on their property in Scotland County. Then she took on the daunting task of building a house nearby to her specifications including tall ceilings, eight-foot-eight-inch doorways, and custom-built furniture.

After she completed her house and took some time to enjoy it, she went back on the road, joining Ringling Bros. World’s Greatest Shows. After that attraction ran its course, Ella Kate exhibited herself at county fairs and other small venues. She died in 1913 at the age of forty from tuberculosis, probably contracted during her travels.

Ella Kate’s story is one of pain, but also one of acceptance—accepting the person she was with no qualms and a lot of courage—and ultimately one of embracing life. Kate Klise’s book illustrates this in a poignant way:

“More than one rude spectator stuck my leg with a pin to see if I stood on stilts. When this happened, I always whispered to myself what Mama and Papa always told me when I was growing up, ‘Stand straight, Ella Kate.’ The more I said it, the better I felt. And the more I saw the world, the more I wanted to see it. Because as big as I was, the world was so much bigger. And I intended to see it all.”

Perhaps it was this acceptance and inner strength that drew Kate Klise to Ella Kate’s story and motivated her and her sister to create their book. “Ella Kate had a Mona Lisa smile,” Kate says, “like she knew something that no one else knew.”

We can all be sure that she did, indeed. Rest in peace, Ella Kate.

Related Posts

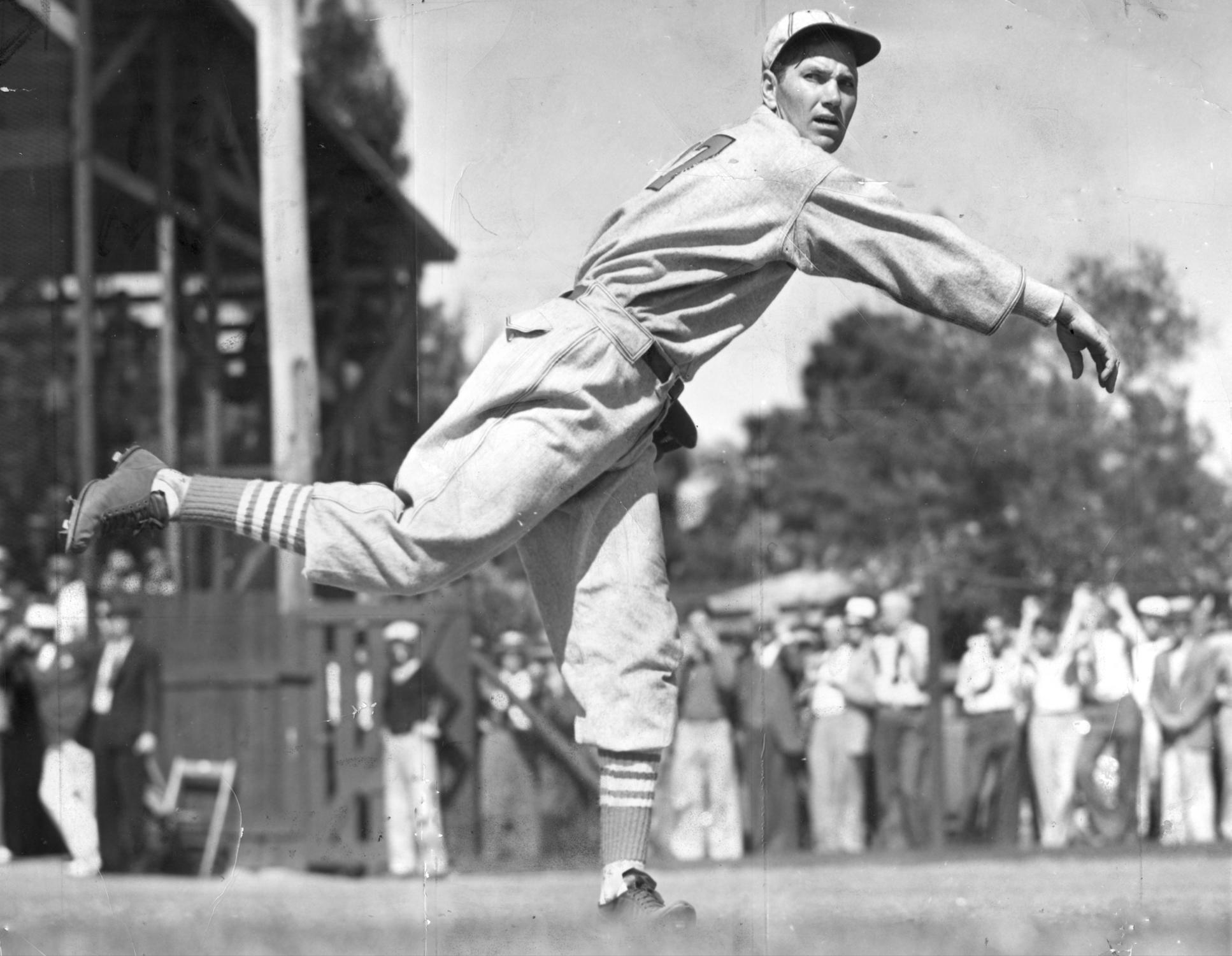

April 12, 1952

It was "Dizzy Dean Week" in St. Louis in celebration of the movie The Pride of St. Louis. Dizzy was in town for the week and said he didn't care if it wasn't exactly accurate.

Paul Harvey: The Rest of the Story

America’s number one talk show host who hails from Cape Girardeau. I’m talking about Paul Harvey, whose daily broadcast The Rest of the Story aired on more than 1,100 radio stations for thirty-plus years.

The Birdman of Salem

Artist David Plank can’t remember a time when he wasn’t drawn to birds. While his boyhood friends were busy kicking soccer balls and hitting baseballs, David was in the woods of Salem with paper and pencil, capturing the details of a perched barn swallow or a purple martin.