The last tribal body of American Indians was removed from Missouri in 1837, but they would make a reappearance in the state during the Civil War. The conflicts that led to their involvement in the war began years before the first shot was fired.

Photo credit: Freepik, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, National Park Service

By Michael Dickey

Missouri was bordered by reservations in the “Indian Territory,” now Oklahoma, and Kansas. The Kansas Territory was formed out of Indian lands in 1854 and opened to white settlement. The border region between Missouri and Kansas became a hot bed of armed conflict between pro-slavery Missourians and abolitionists who wanted to make Kansas a free state. American Indians living in this border region were sometimes victimized by raiding parties. By 1856, many rural Indians found it prudent to take refuge in towns to avoid the “border ruffians” roaming the countryside. This border conflict, known as “Bleeding Kansas,” continued right into the Civil War.

Indian nations were pulled into the conflict, and the issues were complex. Prior to forced removal during the late 1830s, members of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes”—the Cherokee, Muscogee Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole—had adopted many aspects of Euro-American culture, including a slavery-based agricultural system. They took that system to the Indian Territory, and some supported the Confederacy to protect their investments. Others, angry about eviction from their homelands at the instigation of Southerners, sided with the Union. Still others resented their removal by the United States government and became pro-Confederacy. Tribes in Kansas who had been terrorized by Missouri border ruffians were eager to support the Union. In short, Native American nations were as divided as the rest of the country.

SCOUTS FOR THE SOUTH

American Indians had reasons to enlist that went beyond loyalty to either the Union or Confederate cause. First, they were promised pay for their services. They depended on provisions from trading posts to survive, and government annuities were often inadequate or “disappeared” at the hands of unscrupulous Indian agents. Unfortunately, many were not paid regularly, if at all.

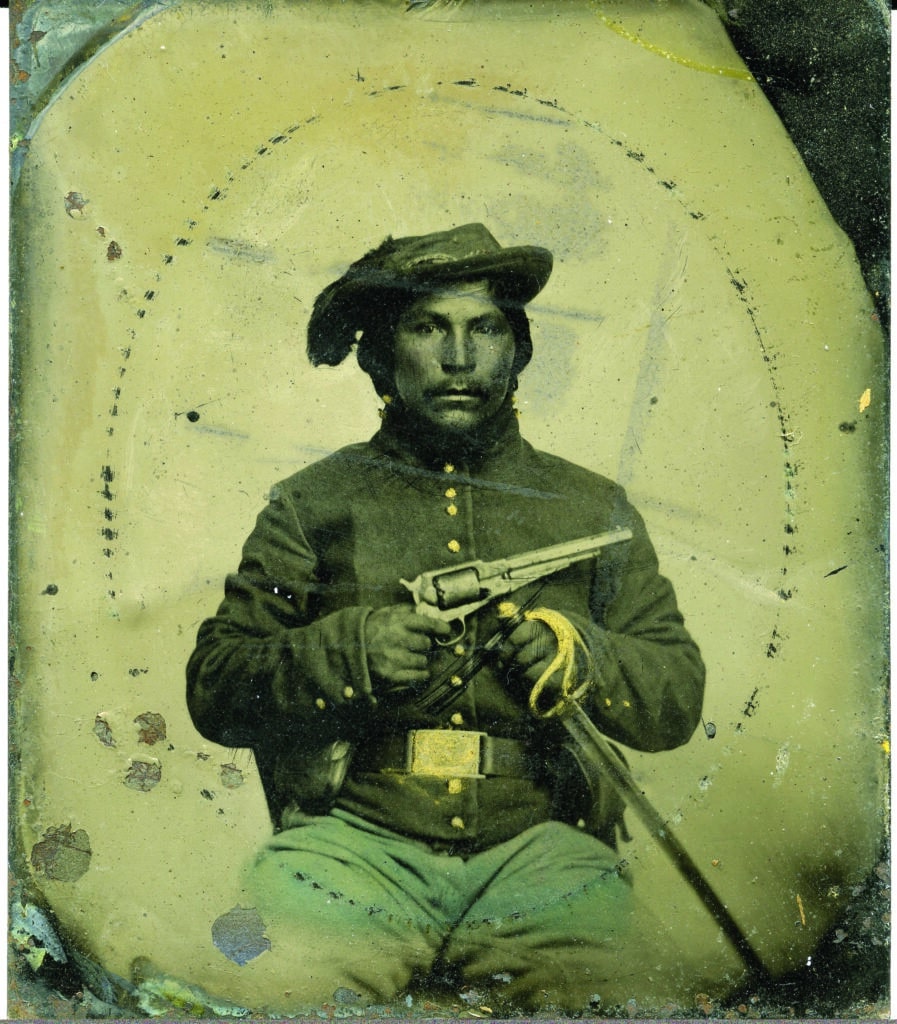

The war enabled young American Indians to escape the monotony of reservation life, where there was often little for them to do. In addition, they culturally retained the old warrior ethic where one proved himself by deeds of valor and bravery. Whatever their reasons for enlisting, American Indians were active in all theaters of the Civil War. But the greatest numbers were concentrated in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, which includes present-day Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma.

This western theater of the war was under the jurisdiction of the US Army’s Department of the West and divided into the districts of Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, and Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Actions throughout the Trans-Mississippi outside Missouri’s borders often had consequences for the state. When the war commenced in April 1861, the Confederate government immediately sought to enlist allies from the Indian Territory, particularly from the Five Civilized Tribes, which were especially numerous. Albert Pike, an Arkansas attorney and politician and later a general, was named Confederate Commissioner to Indian Territory and began raising several American Indian Army regiments for the Confederacy.

Pike’s efforts drew immediate attention in Missouri. On July 15, 1861, the St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican newspaper printed a letter received from Springfield shortly after the Battle of Carthage was fought on July 5. “Missouri has been invaded by troops from Arkansas. The threats of the Revolutionists have been made good. Our state has been invaded by Indians and people from the state of Arkansas.” The letter railed against Missouri’s secessionist Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson and Lt. Governor Thomas Caute Reynolds for “inviting” Arkansans and Indians into the state. The letter writer invoked the fear and hysteria typical of early frontier times. “Bring Indians to burn our dwellings! Bring Indians to murder our women and children! Bring Indians to murder defenseless people!”

Wilson’s Creek, 12 miles southwest of Springfield, was the site of the first truly major battle of the Civil War fought west of the Mississippi River. Missouri State Guard troops under General Sterling Price and Confederate troops under General Ben McCullough were camped along the creek on August 9, 1861. About a dozen or more Cherokee volunteers from the Indian Territory arrived in the camp to act as scouts for the Southern forces. The battle fought on August 10, 1861, was a Confederate victory and it focused national attention on the war in Missouri. Nathaniel Lyon, commander of the federal forces, became the first Union general killed in action.

BARBAROUS ACTS BY ALL

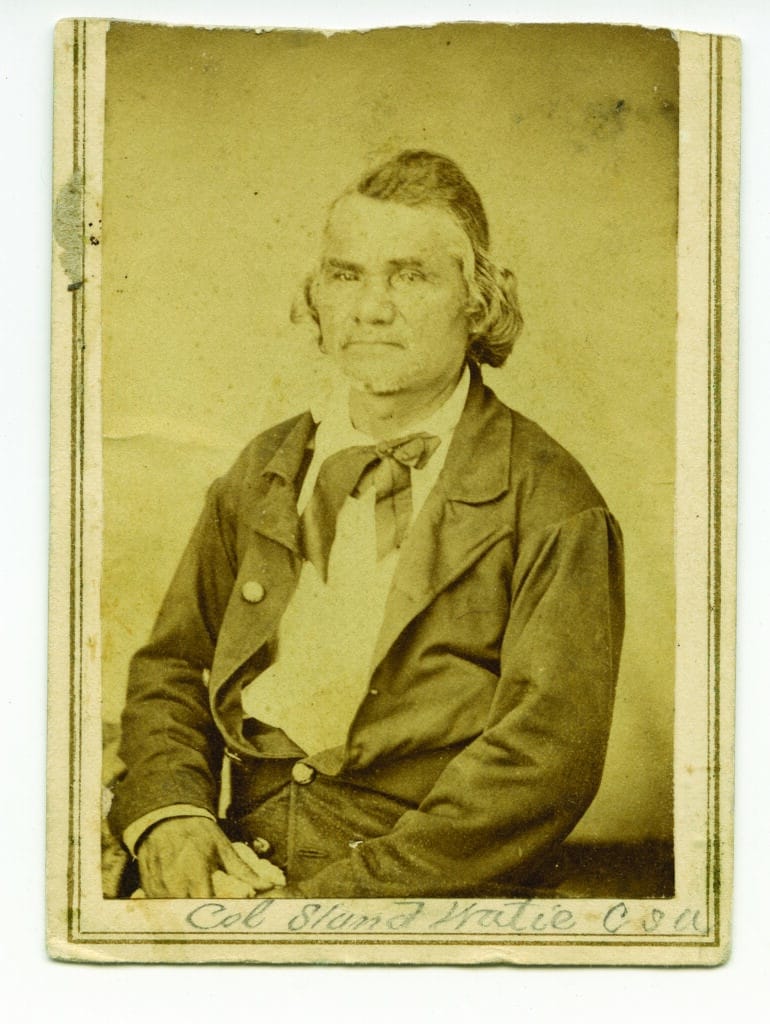

Stand Watie, born Degadoga meaning “Stand Firm,” was an influential leader in the Cherokee Nation. Watie responded to Pike’s recruiting efforts and was commissioned a colonel. He raised the First Regiment of Cherokee Mounted Volunteers in July 1861 and the Second Regiment of Cherokee Volunteers in September 1861. Their ranks included Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw. They fought both federal soldiers and Indians who supported the Union. Watie was often noted for his valor and was promoted to brigadier general in 1864, the only Native American of this rank in the war. He was the last Confederate general to surrender, on June 23, 1865. He was not at Wilson’s Creek, but he and his Cherokee regiments participated in other actions in Missouri.

In the spring of 1862, Confederate General Earl Van Dorn ordered Pike to bring Indian troops to northwest Arkansas. A force of 900 of Stand Watie’s Cherokees joined Confederate forces at Pea Ridge, Arkansas. The Battle of Pea Ridge, also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, was fought on March 7–8. Located just three miles south of the Missouri state line, this battle was crucial in determining which side would control Missouri over the next two years. Pike was a poor military commander and had difficulty keeping military discipline among his Cherokee troops. The Confederates lost the battle and Missouri was secured for the Union. Though some blamed the Cherokees for the loss, it was the deaths of General Ben McCullough and General James McIntosh, along with a shortage of ammunition, that halted Confederate momentum.

The Daily Missouri Republican reported on March 15, 1862, that “many of the federal dead found on the field were tomahawked, scalped, and their bodies shamefully mangled.” The Ottumwa Semi-Weekly Courier on March 20, 1862, reported that the “Indians killed and scalped friend and foe alike,” accusing them of mutilating Arkansas troops in a frenzy directed at white people in general. But these accounts were exaggerated. Only seven soldiers from the Third Iowa Cavalry were confirmed to have been scalped. As the war progressed, Confederate guerillas known as “bushwhackers,” pro-Union Kansas Jayhawkers, and Missouri State Militia troops would commit equally barbarous acts.

Senator James Lane of Kansas began recruiting American Indians for Union service in late 1861. Lane had also organized the first African-American regiments that served the Union. The federal government at first refused to sanction his actions, but relented and endorsed his efforts early in 1862. The First Regiment, Indian Home Guard of the Kansas Infantry, was organized at LeRoy, Kansas, on May 22, 1862. This regiment was composed mainly of Creeks who had fled the Indian Territory.

American Indian troops often modified almost every aspect of military life, including uniforms, drills, and the personal use of government-issued weapons—sometimes subtly incorporating a tribal symbol and sometimes rejecting all military garb and equipment. These acts would have resulted in severe punishment for white troops. But there was a dire need for manpower in the Army, so military commanders accepted the Indians’ behavior in exchange for the valuable service they provided, especially as scouts. Some observers ridiculed the appearance of Indian troops as “comical and ludicrous.” But Indian Agent William Coffin expressed “little doubt that the kind of service required of them they will be the most efficient troops.”

Photo credit: Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, National Park Service

CONFEDERATE DESERTERS

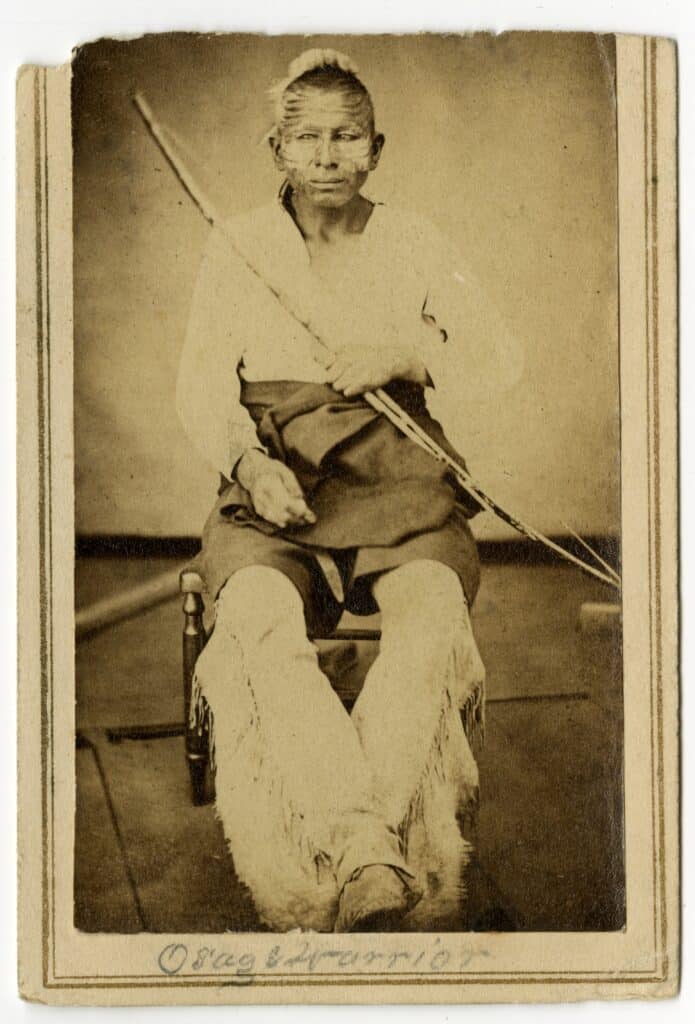

The Second Regiment, Indian Home Guard of the Kansas Infantry, was organized from June 22 to July 18, 1862. They were first assigned to the Department of Kansas then reassigned to the Department of Missouri from February 1863 to February 1864. The Second Regiment consisted of one company each of Delaware, Kickapoo, Quapaw, Seneca, and Shawnee and two companies each of Cherokee and Osage. It took longer to organize this regiment due to the political disagreements of the various Indian agents involved in negotiations.

Unit cohesion was more difficult for officers to manage because the tribes involved spoke different languages, had different customs, and at times in the past had been enemies. Most of the tribes in this regiment had adopted Euro-American culture to a degree. The Osage however were still considered “blanket Indians.” That is, they rejected white culture and maintained their traditions and mode of dress.

The Third Regiment, Indian Home Guard of the Kansas Infantry, was equipped and mustered into Union service at Carthage, Missouri, on September 16, 1862. They were mainly Cherokees who had deserted from Confederate service, as well as loyalist Creeks. The Leavenworth Times newspaper of September 30, 1862, reported that the regiment was composed of 12,000 men. The captains and second lieutenants were Cherokee “men of intelligence. Indeed, the greatest part of the regiment can read and write and can scarcely be called an Indian regiment.”

Second in command of the regiment was Lt. Colonel Lewis Downing (Luyi Tuwanosgi) described as “one of the finest specimens of a man … a full-blood Cherokee who is a leader among them.” Downing started the war as a Confederate but changed sides within a few months. After the war, Downing became the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Most of the activity of the Confederate and Union Indian brigades took place in the Indian Territory or northern Arkansas. However, they were frequently deployed in Missouri as scouts or as skirmishers. On April 26, 1862, about 150 men of the First Missouri Cavalry (Union) skirmished at Neosho with 200 to 300 Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Choctaws under Colonel Stand Watie.

Major J. M. Hubbard of the First Missouri reported a victory to General Samuel Curtis, claiming 32 of the enemy killed or wounded, 62 prisoners and 76 horses captured as well as a large quantity of arms. At the same time, Confederate Colonel Douglas Cooper reported to General Albert Pike:

GENERAL: I have to inclose [sic] Col. Stand Watie’s official report of an engagement between a small party of his regiment and about 300 Federal troops near Neosho, Mo., which resulted in our favor and the retreat of the Federals.

Too much praise cannot be awarded Col. Stand Watie and his brave men for their ceaseless vigilance on the northern line of the Cherokee Nation and their gallantry in attacking and routing a superior force of regular, well-drilled Federal troops.

Watie reported killing 31 of the enemy, capturing three, and wounding several others while he lost only two men killed and several slightly wounded. This incident highlights the claims and counterclaims in the multitude of skirmishes that characterized the war in Missouri. Often there was no clear winner in these smaller engagements.

INDIANS AGAINST INDIANS

Indian Brigades were in General James Blunt’s march through southern Missouri and northern Arkansas from September 17 through December 3, 1862. The Brigades engaged the enemy at Shirley’s Ford and Spring River near Carthage on September 20.

On September 30, General Blunt dispatched some of his 7,000-strong forces, including the Indian Home Guards, toward Newtonia. This would result in a battle pitting Indians against Indians, some from the same tribes.

About 11,000 Confederates, including the 1st Cherokee Battalion under Stand Watie, held the town. They began an artillery duel with the approaching Union forces. General Edward Salomon heard the gunfire in the distance and led the 9th Wisconsin, 6th Kansas Cavalry, and the 3rd Indian Home Guard to reinforce the Union assault. The battle was a stalemate at first, but the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles and the 5th Missouri Cavalry arrived to reinforce the Confederates.

By mid-morning, Union forces began to retreat, some as far as Sarcoxie, 12 miles away. Although Newtonia was a Confederate victory, they did not have the resources to maintain a hold on the area. But the conduct of the service, Indian Brigades during the battle and in covering the Union retreat made a positive impression on the federal troops. Edward H. Carruth, a commissioner who recruited Indians for Union service, wrote:

In this Contest our own regiments now freely acknowledge them [Indians] to be valuable Allies and in no case have they as yet faltered, until ordered to retire, the prejudice once existing against them is fast disappearing from our Army and it is now generally conceded that they will do good service.

The Detroit Free Press of January 28, 1863, printed a report by a Missouri correspondent praising the Indians in General John Schofield’s “Army of the Frontier” operating in Missouri and Arkansas.

These men are mostly Cherokees and Creeks. They are truly a study, with their variety and grotesqueness of costume. Their peculiar features and the traditions and associations that linger around their history … they have clung with a pertinacity and heroism with a self-sacrificing fidelity and patriotism that might well put to shame the loud-mouthed professions of the radicals of the North, who claim so vast a superiority over them in civilization.

They are quite tractable, perfectly obedient, and take readily to military discipline. Yet they do not see the propriety of remaining in ranks during a fight. They say it looks very well on parades, but is too dangerous in fighting. They appeared well on review, and gave the General three war whoops as a salute.

The 15th Kansas Cavalry was formed on 5 September 1863. Company E was made up of Delaware volunteers. They were active in multiple patrols and skirmishes throughout Missouri, primarily engaging guerillas.

They were engaged in operations against General Sterling Price’s forces at Lexington on October 19, 1864, the Little Blue River on October 21, Independence on October 22, and the last major battle to be fought in Missouri—the Battle of Westport—on October 23. They continued the pursuit of Price’s retreating army along the Missouri-Kansas border, finally ending at Newtonia on October 28. The 14th Kansas Cavalry, in which 23 Ioways were enlisted, was also engaged in the Battle of Westport and the pursuit of Price’s army to Newtonia.

Although neglected in history, thousands of Native American troops fought for the Union or the Confederacy. Regardless of which side they served on, they were subjects of fear and racial bias, and they were accused of committing battlefield atrocities. But as the war progressed, their value as capable soldiers and especially as scouts earned them respect among the white Soldiers.

They made an impact in Civil War history that has not been fully appreciated.

Photo credit: Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, National Park Service

LEARN MORE:

THE DELAWARE SCOUTS

Union General John C. Fremont commanded the Department of the West at the beginning of the war. Well known for exploring and mapping the West in the 1840s and 1850s, “Frontier Fremont” had used Delaware Indians as scouts during his expeditions. Fremont recruited 54 Delaware men to act as Army scouts in Missouri. Captain Fall Leaf, who accompanied Fre- mont’s expeditions, now served as his chief of scouts. The Delawares were featured in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on September 26, 1861.

“General Fremont, on taking command in the West in 1861, while he shrank from employing the Indians as soldiers, saw the advantage of using them as scouts, and for this purpose organized a band of them, selecting only the most reliable, robust, and best characterized. They soon made their value known by the early intelligence they brought of the enemy’s movements. Some of them were also employed by General Grant.”

Bands of Delaware had resided in Missouri from 1788 until 1829, when they were removed to a reservation in northeast Kansas. Fremont was replaced by General David Hunter on November 2, 1861. He disbanded the Delaware scouts and sent them home, but the Delaware scouts would be reactivated in 1862. Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole reported that year that of a total of 210 Delaware adult males between the ages of 18 and 45, 170 had volunteered for the Union Army. He added, “It is doubtful if any community can show a arger portion of volunteers than this.”

To read about Opotheyahola, who refused to join the Confederacy, and to explore our reading list to learn more, click here.

Article originally published in the July/August 2023 issue of Missouri Life.

Related Posts

Site of an Early Civil War Battle

The silence that surrounds you at this site belies what happened here during the Civil War. This is where one of the earliest engagements of the Civil War took place. Stand in the spot where the Union fired the final battle shots.

Maple Leaf Festival, Route 66, Civil War Battle, and lots more

Carthage, a town of about 14,400, has more than six hundred homes and historics buildings on the

National Register of Historic Places.

Lexington Invites You to Experience the Spirit of the Civil War

On October 27 Spirit of the Civil War, a community living history event, will truly transform downtown Lexington into its 19th century look and feel. Serving as both a reenactment of the Battle of Lexington and a community fall festival, this event has attractions that will delight visitors of every stripe.