Boone’s Lick State Historic Site is off the beaten track but well worth the trip to visit. We take salt for granted but there was a time that salt was made from boiling down the briny water and then it was shipped to settlements. Learn about salt production at this 50 acre site.

Photo Courtesy of Missouri State Parks

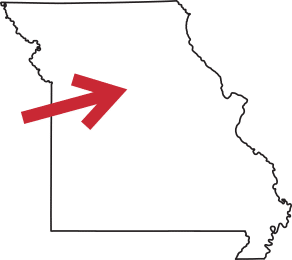

NATHAN AND DANIEL MORGAN BOONE began manufacturing salt at a Missouri valley site in what is now southwestern Howard County in 1805. The Boone brothers later left the salt business, but their enterprise gave these salt springs and this interior region of Missouri a new name. The trail the Boones blazed from St. Charles to the salt springs, known as the Boone’s Lick Trail, was followed by thousands of pioneers who bypassed eastern Missouri to settle the rich farmlands of the Missouri Valley.

Salt springs, or salines, were desirable in a frontier society and common in this part of the state, though few were as large or as well-known as Boone’s Lick. Lewis and Clark recorded “a large lick and salt spring of great strength” about four miles southeast of “a cliff called the Arrow Rock” on their trip up the Missouri in 1804.

In an interview more than four decades later in 1851, Nathan Boone said they initially had six to eight men using forty kettles and one furnace to boil the brine water. They produced twenty-five to thirty bushels of salt a day and boated them to settlements downriver where salt sold readily for two-and-a-half dollars per bushel. As the business grew, they added furnaces and kept fifteen to twenty men employed, making 130 bushels a day. Each worker was paid about fifteen dollars a month.

The Daughters of the American Revolution marked the site of Boone’s Lick in the early twentieth century, but it remained relatively unknown. Then in 1960, Mr. and Mrs. J. R. Clinkscales of Boonville and Horace Munday donated to the State Park Board two small tracts that contained what remained of the salt lick. At first, the site required a visitor to exercise his or her imagination.

Over the following decades, however, there were several important discoveries. In 1986 a brief ten-day archaeological investigation led by Robert T. Bray found not one furnace as in 1961, or two as reported by Nathan Boone, or four as reported by Jesse Morrison, but six rock-lined furnaces. Four years later, another investigation would raise that number to ten. Moreover, the remains of several well casings, two log cabins, and a brine-elevating delivery system were still there underground, perfectly preserved in the waterlogged, briny earth.

Photo by Sarah Hackman

Most remarkable of all was a ten-foot-long octagonal shaft superbly hand-hewn from a log. It was the drive shaft for a tread wheel designed to dip brine from the spring and elevate it to a system of wooden flumes to supply the various furnaces. The 960-pound drive shaft required twelve people to carry it up the hill to be transported.

The park contains about fifty acres set among rolling fields and wooded hills. A kiosk explains how salt was made. A narrow, winding trail among wooded hills leads down into the spring valley. An original cast-iron salt kettle and remnants of two well casings are still visible on site, and the drive shaft can be seen in the visitor center across the river at Arrow Rock State Historic Site. Boone’s Lick today is off the beaten track and so peaceful that you can scarecly imagine it as the scene of a noisy, smoky frontier industry.

Boone’s Lick State Historic site has hiking and picinic areas.

Boone’s Lick State Historic Site

Rt. 187, Boonesboro, MO

Read more about Missouri State Historic Sites here

To purchase the Missouri State Parks Special Edition book, click here.

To purchase the lovely coffe table book, Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites, click here.

Related Posts

Nathan and Olive Boone Homestead State Historic Site

Nathan Boone, son of the famous pioneer, Daniel Boone, and family moved to the homestead in Ash Grove from their estate in St. Charles County. The site is now a State Historic Site and well worth a visit. His cabin, home furnishngs and the gardens are available to tour.

Bollinger Mill State Historic Site

Bollinger Mill and Burfordville Covered Bridge provide you with a step back in time to experience genuine grist milling, a stroll through the oldest covered bridge in Missouri, and a peaceful rest along a tree-lined stream.

Visit the Battle of Lexington State Historic Site

Lexington, Mo is brimming with annetebellum homes and amazing architecture, and is surrounded by beautiful landscapes. The Anderson House was used as a hospital during the Civil War. The site is most notable for the Battle of the Hemp Bales. Come find out why.