The rain started on the eve of the weekend, harmless. Seven inches later, the Big Piney River swelled. When the rain stopped, residents of Devils Elbow sighed with relief. In other parts of the state on that last weekend of April 2017, some ninety-three evacuations were occurring.

But on Sunday morning, the Missouri State Highway Patrol told folks in Devils Elbow to get out, fast. Something big was coming.

Retiree Carmen Debo stood in the window of her early twentieth-century waterfront home and watched the river. A flood was certain—after all, they lived in the floodplain—but it wasn’t her first. She’d lived in Devils Elbow for twenty-five years. Her husband, Bill, grew up down the street. Even though they didn’t have flood insurance, preparations seemed manageable. The Debos moved cars and tractors and boats to the top of their driveway, and then they moved their washer and dryer. As the river crept toward their house, Carmen began stacking photo albums on high shelves. She took dresser drawers, stuffed with clothes, and stored them up high with the photos.

It felt a bit extreme, but better safe than sorry, and surely those shelves, high above her head, were safe.

She was wrong.

By local estimates, the Big Piney River rose a record twenty-eight feet by Sunday before finally retreating. When the Debos returned to their house four days later, two of their cats had died. A box with their birth certificates and land deeds and marriage license was missing. The refrigerator had burst open, leaving a stick of butter stranded on the fireplace mantel. Fearing further damage, Carmen left her soaked photo albums untouched. Down the street, Terry Toula’s house had simply floated off its foundation. Dale and Kate Martin, who just three weeks before had finished building their dream home, returned to find half the deck gone and the backyard gouged with holes large enough to swallow a Volkswagen. The only downtown house spared—perhaps saved by the grace of about a foot of elevation— belongs to Bruce and Nancy Frazier, who offered laundry services in the immediate aftermath. Pitted and debris-strung, every road in Devils Elbow looked like a bombing target. Television sets and Christmas ornaments and photo albums hung from the underbelly of the town’s famous steel truss bridge, deposited by water that had risen to its beams.

Lawson “Smitty” Smith, the Pulaski County emergency manager, surveyed the damage and declared: “Devils Elbow is gone.”

To be fair, it was barely there in the first place.

Before the flood, an ill-timed blink might have masked Devils Elbow from the gaze of a passing motorist on Route 66, an old section of which still goes through the town. It’s just a few narrow streets and some Mayberry-esque homes flanked by empty lots and grand shade trees. There used to be a boarding house, from the late 1940s, with a downstairs dance hall and market called McCoy’s, but it’s been abandoned for years. Only two businesses are open year-round now—the post office and the bar. Until recently, the post office doubled as a general store, so long as your needs stopped at cigarettes and soda. The community’s main artery is a section of the original Route 66, which stretches across the Big Piney River and passes the Elbow Inn Bar & BBQ, whose famous bra-adorned ceiling has earned a loyal following from tourists as well as the locals—all 66 of them (or 56, or 76, depending on whom you ask).

Terry Roberson runs the Elbow Inn. With his barrel of a chest, he looks exactly like a man destined to run a biker bar in the rural Ozarks. Once prompted, he’ll deliver soliloquies on the town’s colorful past, starting with the opening: “You know how the Elbow got its name, right?”

Pre-1900, the Ozark Mountains provided an abundant supply of timber for railroads, and rivers were the easiest mode of transportation for logs. Ties floating down the Big Piney regularly caught on a stubborn rock at the river’s sharpest bend. Lumberjacks nicknamed it a “devil of an elbow,” and the adjacent community—formerly called Pine Bluff and, before that, Hunter Hollow—adopted the curse with pride. Perched on the scenic river and armed with a peculiar name, the town soon became a recreation hotspot for fishing and hunting. When Route 66 arrived in 1926, the Missouri Planning Commission designated Devils Elbow as one of the state’s seven wonders.

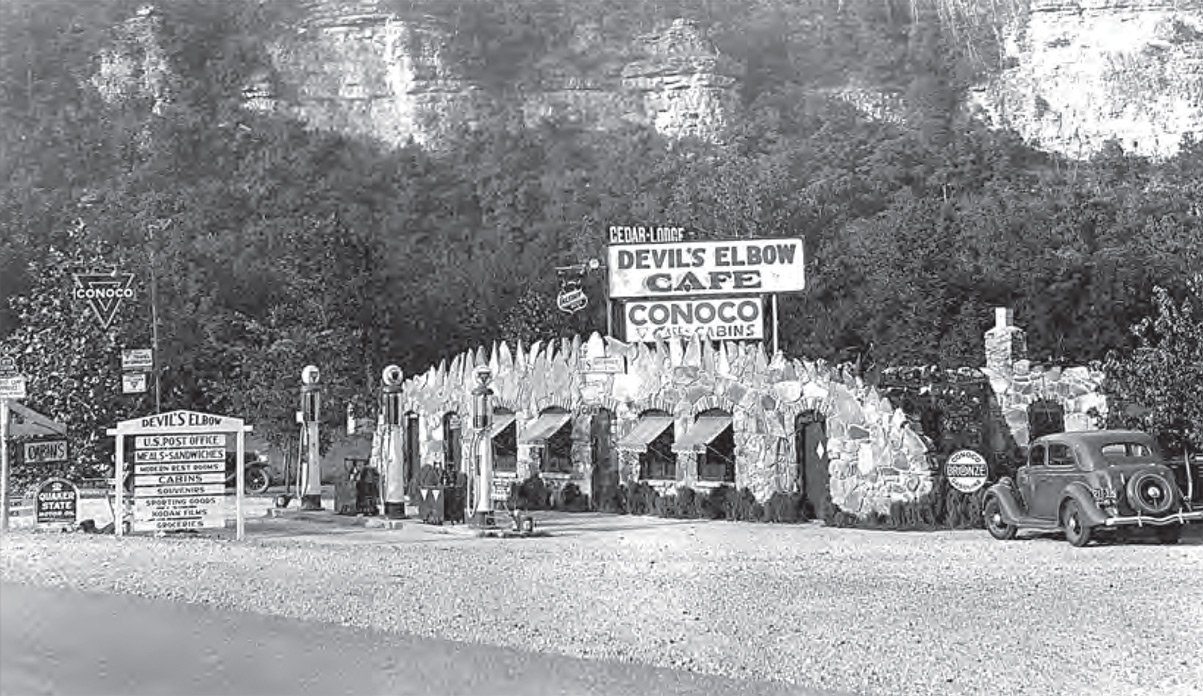

For the next three decades, the community boomed. The post office became a destination for travelers thrilled by the sight of “Devils Elbow”on the postcards. Tourists stopped at the Hillbilly Store for Ozark novelties such as arrowheads and walnut bowls. Barbecue wafted in the air around the Munger-Moss Sandwich Shop (currently the Elbow Inn, which reopened its patio on Memorial Day weekend after recovering from flood damage), drawing lines out the door. Rench’s Cedar Lodge sold Kodak film and twenty-five-cent meals. Next door, McCoy’s Market hosted weekly dances (due to rowdy crowds, these were short-lived). Across the street, the Hiawatha House doubled as a hardware store with upstairs lodging. Its owner, E.D. Tarbell, was an amateur astronomer whose telescope and observatory sat in the backyard. At Ernie and Zada’s E.Z. Inn, motorists could buy a tank of gas, book fishing and hunting expeditions, rent a room, and spend the evening dancing. The surrounding hills were filled with artisans specializing in basket-making and boat-building. Nearby was a two-room schoolhouse and a church that conducted baptisms in the river. For residents, it was paradise on earth—a place where people looked out for, and sometimes reprimanded, other people’s children.

Yet for all of the small-town charm, Devils Elbow was rough around the edges. Trucks navigated the crooked streets and steep hills so slowly, people would jump on the backs and rob them, according to a 2007 article in the Old Settlers Gazette. The Devils Elbow Cafe served liquor for eleven months starting in 1945, but the venture overwhelmed the owner, who logged more than one hundred fights before shutting down because the patrons “played too rough.”

The town grew through the buildup of Fort Leonard Wood, which brought thousands of men and families to Pulaski County. Many settled in the Elbow. Then, in 1943, wartime supply transport required a four-lane highway, so Route 66 was relocated a mile north. The single mile made Devils Elbow that much more removed. Losses compounded as post-war tourism dropped in the late ’50s. When Interstate 44 steamrolled across the state in the 1970s, the last remaining handful of local businesses fled to the freeway.

And then came the floods.

The catastrophic 1982 flood was termed a 500-year event, something that would only come around but every half millennia. That record broke in 2013. And again in 2015. And then again in 2017.

Many pinpoint the floods as catalysts of the town’s decline. Residents blame factors such as climate change and watershed saturation. They say that, way back when, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources stopped dredging the Big Piney, which contributed to the flooding. State officials, though, say they’ve never dredged the river. Still, the debate surrounding the causes of flooding distracts from the town’s real problem: a decline that has spanned more than half a century.

“Everybody keeps saying Devils Elbow is gone and blah, blah, blah—not if I have anything to do with it,” says Angie Hale. “Devils Elbow is our town. Period. It’s our town. It’s not going to go nowhere.” The Illinois native has lived here since 2004, but her family vacationed in the area when she was a child. These days, Angie is a summertime canoe outfitter. The rest of the year, she’s a bail bond agent. Immediately after the April flood, she oversaw volunteer teams, food donations, and supplies.

The top priority following the flood was road repair, so residents could access their homes to begin cleanup and assess damages. An immediate response from Pulaski County was expected, but officials were overwhelmed with flood-related problems. This wasn’t unusual—several Devils Elbow residents say they feel regularly ignored by the county. “Basically, we’re always last on the totem pole,” Angie says. Armed with reassurances of eventual federal aid and reimbursements, citizens relied on civilian and military volunteers to begin picking up the pieces.

“When people needed something, we got it for them,” Jim Woodman recalls. “We didn’t come in and say, ‘Well, we’ll see what we can do.’ We just did it.” Although Jim is the Rolla postmaster, he volunteered one hundred hours on a tractor that first week. But that sort of grassroots action shouldn’t have to be the first line of restoration, he argues, because it’s the county’s responsibility to serve constituents by shouldering costs.

Jim, Angie, and a handful of Devils Elbow residents attended a June 1 Pulaski County Commission meeting seeking answers. When would they repair the roads? Pay for gravel? Reimburse residents for cleanup? At the top of the meeting, Angie argued that residents shouldn’t bear the cost of removing large items such as cars, appliances, and housing debris that had washed downstream. The response from the commissioners was frank—life isn’t fair, and there’s only so much a cash-strapped county can do to help.

“I’ll tell you what this is called; it’s the main thing—a disaster,” Western District County Commissioner Rick Zweerink said at the meeting. “I can’t make it right. You can’t make it right. It is what it is. We will help what we can. You think you’re the one left behind, but Pulaski County ain’t high on the list. For four years we’ve been waiting, waiting, waiting. Nothing’s happened.”

According to the county commissioners, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) still owes Pulaski County $1,078,000 in reimbursements from the 2013 and 2015 floods. Reimbursements must be made for each individual project—each bridge, each road, each culvert. FEMA says the paperwork from Pulaski County is missing or completed incorrectly or that the projects themselves fail to meet federal standards.

Federal-level attention has trickled in. Congresswoman Vicky Hartzler visited Devils Elbow shortly after the flood, posed for photographs, and collected letters written by residents. Her office says Rep. Hartzler had “a very productive meeting with FEMA officials” in June. Before the April flood, she sponsored a bill that has been waiting on a Senate vote that would require FEMA to submit reports to Congress. In the meantime, after years without FEMA reimbursements, Pulaski County’s funds have run dry.

“My suggestion is if you’re sitting here waiting for someone to help, you’re going to be waiting,” County Commissioner Gene Newkirk trailed off at the meeting, and then added: “Good luck with that. I’ve about lost my health with this deal.”

Patience faded. Kate Martin turned to her husband and announced, “I’m done,” then stormed out of the meeting. As the minutes passed, more residents left, gathering in the lobby or just outside the courthouse.

“I’m tired,” Jim admits. “The last thing I want to hear out of their mouths is, ‘We don’t have the money.’ The residents don’t have money either, but they’re finding a way.”

Money is an obvious problem, but what Devils Elbow residents seem to crave most is affirmation. That fight hasn’t been entirely fruitless. In 2012, the Pulaski County Tourism Bureau ran a “This Place Matters” campaign, partnered with the post office as it faced the threat of closing. The following year, the county spent $1.3 million dollars restoring the bridge. Hopes buoyed recently when landmarks such as the bridge, the Elbow Inn, the post office, Big Piney Cabins, and more were added to the National Register of Historic Places just last April. Many hoped the designation would boost tourism and possibly spark development.

But the flood hit two weeks later. Now, dreamy talk of Devils Elbow’s economic revival seems too abstract to entertain, and stunned residents are focused on returning to the way things were—a tranquil life absent of floods and change and government intervention.

“I would like to think that in twenty, thirty, fifty years, we’ll still have what’s there,” says Ruth Keenoy, a St. Louis-based freelance preservationist. “The fact that people are carrying on after this incredible flood is a good indication. It’s such a beautiful area, and it always was an attraction for people, even before Route 66. I think it’ll make it.” Ruth penned the National Register of Historic Places application for Devils Elbow.

Others have different ideas about how the community might bounce back. “The history of this place is the history of this country,” says Randy Becht, economic development director of the Pulaski County Growth Alliance. “What it evolves into we’re not sure, but this place is too special not to evolve into something.” Perhaps, he muses, a state park might generate similar economic effects that the Katy Trail delivered. Right now, talk of a state park is just that—talk—and would involve employing the Missouri Buyout Program, which requires widespread community support and partially matching funds from the cash-strapped county.

The idea of a buyout is appealing to residents like Bill Debo, who lost everything in the flood, because buyout valuations match pre-disaster estimates. “I’m the guy with the devil’s tail on,” Bill says. “I’d love to see the whole thing bought out. Make it a state park. Some people get mad when you mention selling out. You ever been around a bunch of old hard-line landowners? Remember the National Streams Act? I don’t know what the deal is—[my neighbors] want to own the land. They want to own it. They want to go back to the ’50s. You can’t do that.”

Returning to the past means different things to different folks. For some, restoring the relative isolation of pre-flood order is enough, so long as they can continue their lives in peace. Others want to see the town not only survive, but thrive.

Stretching the town’s fingertips back out to Route 66 seems to be the key to stimulating more restaurants, motels, stores, and tourism outfits. According to the state Division of Tourism, Missouri hosted more than 400,000 international tourists in 2016, and Route 66 appeals to those chasing the romanticized open road and small-town America depicted in TV shows like Route 66 and in movies such as Disney’s Cars. The National Park Service has long considered making Route 66 a national automobile trail, but congressional budget cuts have made achieving that designation challenging.

Small towns hold a sacred status in the American psyche, so watching them die is a fate so painful it seems unthinkable.

Communities like Devils Elbow are hunting for sustaining industry. Devils Elbow residents are turning to Route 66 as an untapped market, but there’s a reason growth has been elusive so far. Even though economic opportunities along Route 66 certainly exist, Devils Elbow is now twice removed from the highway, and it is inconveniently positioned for most casual Route 66 tourists.

But the potential is there. Even after the floods, it’s not uncommon to see a meandering rental convertible filled with German or Chinese tourists stop on the bridge to pose for a photo. “We read about Devils Elbow in the Route 66 Adventure Handbook and the EZ66 Guide for Travelers,” says Lex Edie, an Australian tourist who explored Route 66 in 2010 and considers Devils Elbow one of the highlights of his trip. “The first thing that we were interested in was the old bridge, then the Elbow Inn. We really enjoyed it, loved that the bridge is still in use, and had lunch at the inn.” Luckily, the floods have not caused long-term damage to the landmark bridge.

Angie would love to capitalize on people like Lex Edie. Ideally, she’d relocate her river outfit to downtown Devils Elbow. And since she’d be right on Old Route 66, she likes the sound of a nostalgic ice cream parlor. But that dream can’t materialize until she has the property, and no one wants to sell. Even Bill Debo, who is interested in a buyout for state park land, can’t bear the thought of selling. He turns down offers every week because, he says, “I’m picky about my neighbors.”

For the few plucky entrepreneurs who might settle there, current tourist traffic barely supports existing enterprises. In addition to commercial property scarcity, the Elbow lacks schools, grocery stores, and gas stations. Most downtown lots fall in the floodplain, and strategic construction requires significant flood-proofing investments plus mandatory flood insurance. Even for those who can afford those extra measures, there’s still no guarantee against inevitable catastrophe.

After the 2015 flood, County Surveyor Don Mayhew recommended several Devils Elbow residents elevate their homes by at least two and a half feet. But the most recent wave of flooding exceeded the base flood elevation by nine feet. “I feel for those people; I empathize with them completely,” Don says. “But the truth of the matter is that there’s not much that can be done. Mother Nature’s going to do what she wants to do, and there’s not much we can do about that. Folks want a solution? The solution is to get out of the floodplain.”

Some people have. At its peak, Devils Elbow boasted several hundred residents. Now, there’s just a handful left. With an aging population primarily in their sixties and seventies, the town risks extinction by the mere mortality of its own residents. For years, children of the town have fled to larger cities, pursuing better education and job opportunities and homes that aren’t subject to the whims of an unpredictable river. Few return.

Terry Roberson stated in bed for three days after the flood. The Elbow Inn would need somewhere around $50,000 to rebuild. An online campaign raised roughly $5,000, and passing motorists are generous with donations, too. Gravel deposits from the river also offered financial consolation; Terry sold 1,000 loads for $60 a piece. He re-opened the Elbow Inn’s patio to the public on Memorial Day, and throngs of loyal patrons and tourists attended. For the foreseeable future, the bar will be open on the weekends.

During the week, Terry is focused on repairs to the town and to his bar, but he’s happy to sit and talk with visitors. Perhaps no one is better positioned to lead the town’s revival, whatever that might be, than Terry. Armed with an encyclopedic knowledge of its past, he’s the gatekeeper to the town’s significance. Conversation tilts toward those who put Devils Elbow on the map—Sterling Wells, the Millers, the McCoys, the Tarbells. But they’re gone now, and the ground their businesses stood on is too often an empty lot where something used to thrive.

“I’m struggling hard to think what could be the savior, what could be the next chapter in the story,” Terry says. “It seems like we’re just recounting all the old chapters. But I do love it here.” Even for the most sympathetic ears, it’s hard to glean meaning from distant strangers of the past who lived in buildings that no longer stand.

Watching the peaceful river slip by the bar’s patio, another life seems unimaginable. It’s unlikely that Terry will ever leave Devils Elbow. But as time moves forward, it might leave him. The river, with all its menace and might, keeps rolling along, chipping away at the shoreline and the town. Terry grew up on the Mississippi River, hunting ducks and fishing for fifty-pound flathead catfish.

He could have retired anywhere. He could have returned to his roots, but he didn’t. Like everyone else living here, he loves Devils Elbow, the town and its history and its ghosts. How could he turn his back on them now?

“One of the biggest thrills I ever caught was a twenty-two-inch smallmouth right here. From the bank. Biggest smallmouth I ever got,” he says. “And I let it go.”

Related Posts

Game On!

They say the house always wins, but community takes the jackpot at Vintage Vegas Casino Night. Sponsored by Vision Carthage, the event features food, drink, and plenty of casino-style fun. Proceeds benefit local charitable initiatives.

Better Together

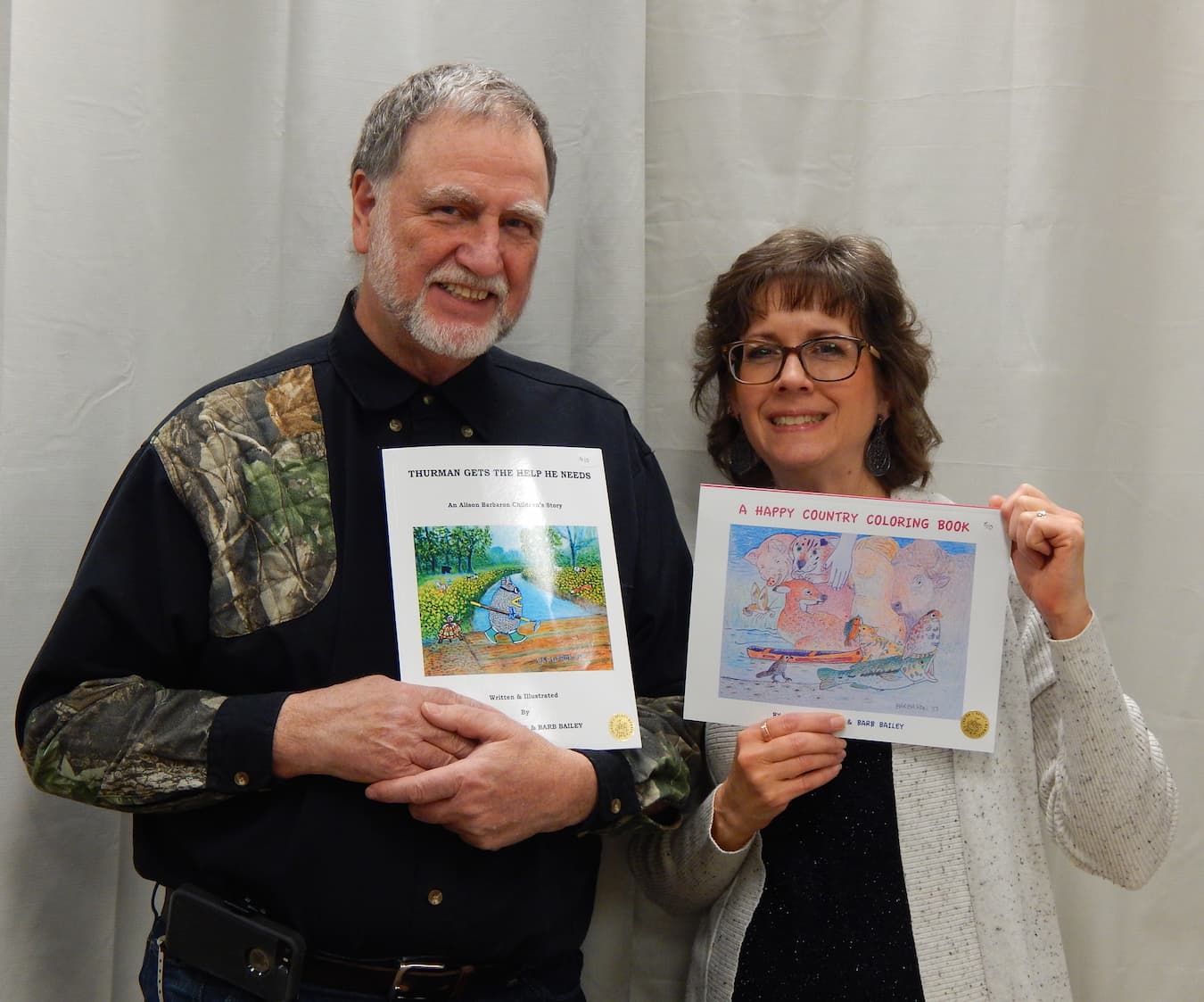

These two Cape Girardeau painters write and illustrate children's books in an unconventionally collaborative way. Their method is a fast-paced give-and-take that requires absolute trust, open minds, and a willingness to pick up and pivot.

MO News is Good News – April 19, 2024

Big things are always happening in Missouri. In this week’s headline roundup, we’ve got big bugs, big fish, big money, and your big chance to land on national TV.